From time to time, most of us struggle with anxiety. Unexpected and unwanted things happen, and we can become very challenged in making sense of this interruption into the daily pattern of life. Surprising events churn up feelings that we may find very confronting, and anxiety can act as a kind of ‘psychological static’ that masks these feelings. This can be a way of our psychological system protecting us from unwelcome feelings, but it also means we often can’t readily discern the emotions that run underneath our anxious state, making it harder to make sense of what we are experiencing.

At the time of writing, there is a serious pandemic happening all around the world, resulting in many people living in a state-directed lockdown situation in their homes. For most of us, these events are unprecedented. Moreover, there is much unknown about the virus, and the long-term effects (health-wise and economy-wise) of this pandemic. As a consequence, it is a very anxious time for many people.

Given the seriousness of the current situation, we can all expect to experience worry at some level. But unchecked, worry can very easily spiral into the red zone of extreme anxiety. If this is the case, what might we do? More specifically, what practical measures can we undertake to find ways of metabolising ‘red zone’ anxiety into something more manageable? What follows are some ideas that could help.

1.Talk to your anxiety

Anxiety tends to be quite a diffuse physiological state, which we experience because of fears and feelings that get stirred up. Once we get into these states, we often become very concrete in our thinking, making it harder to prune back the anxiety to see the underpinning fears and feelings. Asking ourselves what the possible sources of the anxiety might be, and letting our mind imagine what those might be, without judgment, can be a useful way of exploring what lies beneath.

One way of doing this is to creatively imagine your anxiety as a separate person or being, and to ask this ‘person’ what he or she might say about how they are feeling, and the sources of their fears. Allowing your creative imagination to work in this way can be a helpful way of getting beneath the anxiety to reveal deeper fears and feelings. In the current situation, anxiety might be traced a fear of losing control or of facing the unknown. Whilst there is no easy panacea for these kinds of fears, being able to identify them as a cause of anxiety can also help to reveal and manage the associated feelings of sadness and anger that may go along with them.

2. Limit your access to things that trigger your anxiety

A difficulty with anxiety is the way it can act like tumbleweed: hurtling along at great speed, picking up various bits of detritus, getting bigger and bigger. An important question to ask ourselves at times of crisis is whether we are perhaps engaging in activities that might fan this anxiety. For example, are you reading or watching too many news reports? Are groups or individuals you communicate with by text or online supporting you, or are these communications subjecting you to more anxiety when you are already in a vulnerable state? When society is in a state of great worry, fear can become very contagious, spreading like wildfire through the various forms of communication that so many of us rely upon in our day to day lives (Parkinson and Simons, 2012). Sometimes, it pays to limit our access to these forms of communication in order to find more stable ground internally.

3. Try and find time to do something creative

Finally, it’s important to think about the way we are using our time when in a state of anxiety. Anxiety is something that we tend to experience at both a psychological and physiological level. One way of finding a more peaceful state of mind and body is to occupy ourselves with creative activities—pursuits that you perhaps used to enjoy but can rediscover, or new ones that you always wanted to explore. Feeling of happiness and contentment are very much entwined with ‘doing’ and often doing something that challenges us, as well as engaging our creativity and playfulness (Seligman et al. 2005).

Useful links

TED talk on dealing with anxiety

https://www.ted.com/talks/olivia_remes_how_to_cope_with_anxiety/transcript?language=en

Short blog on the benefits of talking to ourselves

https://psychcentral.com/blog/talking-to-yourself-a-sign-of-sanity/

References

Parkinson, B., & Simons, G. (2012). Worry spreads: Interpersonal transfer of problem-related anxiety. Cognition & Emotion, 26(3), 462-479.

Seligman, M. E. P., Steen, T. A., Park, N. & Peterson, C. (2005). Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist, 60(5), 410-421

Whilst there has been much more talk about mental health in the media in the last few years, telling others that one ‘goes to a therapist’ tends to be something that we shy away from, as if there is something embarrassing about needing the help of another to make sense of our struggles. It seems to be much more socially acceptable to tell people about physical maladies we experience, rather than problems we are experiencing in our psyche. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that exploring psychological wellbeing is something that takes us into the realm of the invisible: our inner world.

Whilst there has been much more talk about mental health in the media in the last few years, telling others that one ‘goes to a therapist’ tends to be something that we shy away from, as if there is something embarrassing about needing the help of another to make sense of our struggles. It seems to be much more socially acceptable to tell people about physical maladies we experience, rather than problems we are experiencing in our psyche. Perhaps one of the reasons for this is that exploring psychological wellbeing is something that takes us into the realm of the invisible: our inner world. The title of this review could be ‘Why we all need to read more books about death’. This is because a book like Paul Kalanithi’s reflective journey, following a diagnosis of incurable lung cancer, is a poignant reminder that when we lose sight of our mortality, we can also too easily lose sight of what is important, and what is not, in the way we live. Keeping our eyes averted from the inevitability of our own death (even if we hope it is a distant event) can have the strange effect of making our daily lives less lively, more deadened, as we become weighed down by minutiae of everyday living and our well worn habits.

The title of this review could be ‘Why we all need to read more books about death’. This is because a book like Paul Kalanithi’s reflective journey, following a diagnosis of incurable lung cancer, is a poignant reminder that when we lose sight of our mortality, we can also too easily lose sight of what is important, and what is not, in the way we live. Keeping our eyes averted from the inevitability of our own death (even if we hope it is a distant event) can have the strange effect of making our daily lives less lively, more deadened, as we become weighed down by minutiae of everyday living and our well worn habits. Whatever the stage of parenting one is at, there is a plethora of (often conflicting) advice out there about how best to go about it. The maxim goes that we write about what troubles us: if this is the case, then clearly parenting is something that bothers a lot of us.

Whatever the stage of parenting one is at, there is a plethora of (often conflicting) advice out there about how best to go about it. The maxim goes that we write about what troubles us: if this is the case, then clearly parenting is something that bothers a lot of us. Addiction is a word that causes great fear—to be addicted indicates a compulsive need or drive towards something that promises good feelings but actually, over time as a habitual pattern develops, causes the addicted person great harm. In the past, addiction tended to be viewed as a moral weakness, experienced by some people in society: ‘weak’ addicts were to be pitied (and perhaps privately derided) by ‘strong’ non-addicts.

Addiction is a word that causes great fear—to be addicted indicates a compulsive need or drive towards something that promises good feelings but actually, over time as a habitual pattern develops, causes the addicted person great harm. In the past, addiction tended to be viewed as a moral weakness, experienced by some people in society: ‘weak’ addicts were to be pitied (and perhaps privately derided) by ‘strong’ non-addicts. There is no light without shadow and no psychic wholeness without imperfection. To round itself out, life calls not for perfection but for completeness; and for this the “thorn in the flesh” is needed, the suffering of defects without which there is no progress and no ascent. (C.G Jung, Collected Works, Volume 12, para 208).

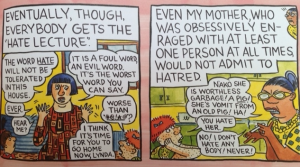

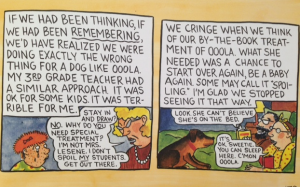

There is no light without shadow and no psychic wholeness without imperfection. To round itself out, life calls not for perfection but for completeness; and for this the “thorn in the flesh” is needed, the suffering of defects without which there is no progress and no ascent. (C.G Jung, Collected Works, Volume 12, para 208). The English-speaking world has been a bit slow on the uptake regarding graphic novels. If you go into a bookshop in France, on the other hand, you will find a huge variety of graphic novels and comics in multiple genres, for all ages. The selection in the UK is getting much better, although I still feel hard done by when I compare the pickings in mainstream bookshops here, with what is available in France (along with regretting my lack of focus during French lessons at school).

The English-speaking world has been a bit slow on the uptake regarding graphic novels. If you go into a bookshop in France, on the other hand, you will find a huge variety of graphic novels and comics in multiple genres, for all ages. The selection in the UK is getting much better, although I still feel hard done by when I compare the pickings in mainstream bookshops here, with what is available in France (along with regretting my lack of focus during French lessons at school).

As a student, I once babysat for a local couple. I recall the experience as bemusing, for almost every available surface in the small house was covered with sticky notes on which were written rousing motivational slogans. It felt rather spooky walking about the house, and encountering endless exhortations. I still recall the one on the bathroom mirror that read ‘You WILL become a millionaire, within the next THREE years!’

As a student, I once babysat for a local couple. I recall the experience as bemusing, for almost every available surface in the small house was covered with sticky notes on which were written rousing motivational slogans. It felt rather spooky walking about the house, and encountering endless exhortations. I still recall the one on the bathroom mirror that read ‘You WILL become a millionaire, within the next THREE years!’ The unpleasant feeling we get when bored, of being in some kind of empty space where time stretches endlessly forwards, is captured well in Charles Simic’s poem:

The unpleasant feeling we get when bored, of being in some kind of empty space where time stretches endlessly forwards, is captured well in Charles Simic’s poem: