The English-speaking world has been a bit slow on the uptake regarding graphic novels. If you go into a bookshop in France, on the other hand, you will find a huge variety of graphic novels and comics in multiple genres, for all ages. The selection in the UK is getting much better, although I still feel hard done by when I compare the pickings in mainstream bookshops here, with what is available in France (along with regretting my lack of focus during French lessons at school).

The English-speaking world has been a bit slow on the uptake regarding graphic novels. If you go into a bookshop in France, on the other hand, you will find a huge variety of graphic novels and comics in multiple genres, for all ages. The selection in the UK is getting much better, although I still feel hard done by when I compare the pickings in mainstream bookshops here, with what is available in France (along with regretting my lack of focus during French lessons at school).

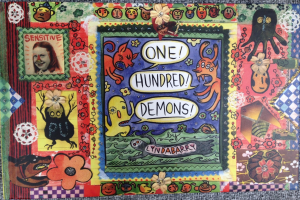

Lynda Barry’s book “One! Hundred! Demons!” is excellent example of how a combination of images and text can communicate a narrative that would be impossible to tell through text alone. The book starts by Barry outlining how she was inspired by Zen Monk’s scroll painting of one hundred demons to experiment with letting her own inner demons to emerge from beneath her paintbrush onto the page.

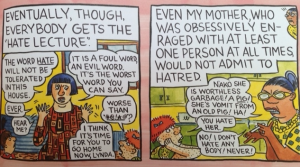

The book is a collection of 17 vignettes or short stories of poignant life experiences that have shaped Barry, and continue to haunt her in some way. The stories are very moving, as well as bristling with philosophical and psychological questions about how we live our lives and relate to others. One of my favourite vignettes is entitled ‘Hate’. In this ‘Demon’ Barry ponders why it is that adults are so keen to rebuke and quash children’s expressions of hate without any understanding or exploration, even though it is clear that it is a core feeling we all experience. Barry recalls the honesty with which, as a child, she and her peers would express their feelings, “When we got mad we couldn’t hide it. It was normal to hate each other’s guts at times”. Expressing these deep feelings, however, was not acceptable to surrounding adults. As Barry puts it, ‘Eventually…everybody gets the “Hate Lecture”. In Barry’s storyline, it’s the mother of her friend who dishes this out following overhearing their fight: “The word Hate will not be tolerated in this house. Ever. Hear me?” a lecture which was swiftly followed by sending young Lynda home.

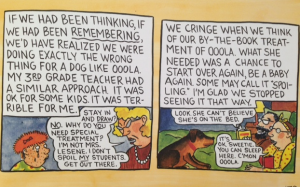

The vignette “Dogs” is also quite brilliant. On the surface, it’s a story about Barry’s experience with rehoming a shelter dog, Oola. Under the surface, it is a story that teachers and parents could also learn much from. Oola had experienced violence at the hands of a previous owner and arrives at Barry’s house aggressive and fearful. Barry describes liking the dog, but being unsure how to proceed with training. Overwhelmed with advice from dog training books, she and her husband set about using the various draconian methods recommended to establish the all important ‘dominance over dog’. Eventually, however, Barry realises that this ‘by the book’ treatment of Oola is not working. Treating Oola harshly was also entirely at odds with her own childhood experience that it was kindness and understanding by teachers that served as some kind of countermeasure to the cruelty Barry had experienced in her own home.

In her introduction, Barry ponders the question of what the book is: “Is it autobiography if parts of it are not true?” followed by, “Is it fiction if parts of it are?” The demon looming on the other side of the table as she ponders these questions seems not particularly interested in answering this conundrum; it stands waiting, needing to be to be drawn. And thereby understood.